Inés Francom

News Editor

Finances are simply part of life. From buying your morning coffee, ordering clothes on Amazon, or getting a job, money is everywhere. There’s no getting around our world without some knowledge of credit cards, direct deposit, high-yield savings accounts, investing, taxes, and some even more confusing stuff, unable to be named in a shortlist.

This is part of why people find the transition from environments like high school to the real world so startling and often complain that school didn’t prepare them for the real world. There’s been a cry for years across the country for more required economic classes to be taught to students. An outcry that North Carolina (NC) attempted to answer with the extension of a former course in the shape of the required course Economics and Personal Finances (EPF).

The idea of an EPF class is great and a huge step forward for NC students, as knowing finances is a skill everyone should know, but the actual execution of this class has been anything but great. In a class that is often spent scrolling on TikTok or using it as a study seminar, students are doing just about anything except learning economics and personal finances. While this plays into the larger problem of student engagement in classes throughout schools, it also serves to show that students aren’t actually learning what the state wants them to learn.

A big part of this problem is staffing. When NC created the class EPF out of nowhere, they didn’t think far enough into the logistics of the class for it to be functioning properly. The idea was that since there used to be a class taught in the social studies department named Civics and Economics, Economics and Personal Finances should be taught there. However, when they initially made the course, NC didn’t really take the initiative to hire any new employees. Instead, they expected current teachers to switch to entirely new courses and learn everything they needed to know about economics in a 40-hour training session.

Although the teachers assigned to these classes are enthusiastic and open to taking on this challenge, they are at no fault for this; they simply don’t have the prerequisite knowledge to teach an economics class. Most teachers who work in the social studies department study to teach history. They’re prepared to teach students about wars, changes in cultures over time, different types of government, geography, and law. This paints a picture that EPF, with its numbers and statistics, doesn’t fit in as it distinctly stands out from the other social studies classes.

The average person barely understands the ins and outs of economics, and to be able to explain such a complicated topic in simple terms, you’ve got to be almost an expert, something you can’t achieve in just the week’s worth of training given to new economics teachers. On top of that, most Economics and Personal Finances teachers seem to be new teachers in general, making it an even more difficult task.

The timing of the course is also not well thought out at all. Many students take EPF in their senior year as that’s when it’s required, but lots of the topics covered in EPF would be better suited for juniors to be learning. For most seniors who are applying to colleges, for scholarships for financial aid and Free Application for Student Federal Aid (FAFSA), legal contracts and loans can be confusing. It’s important for students to learn about loans and how they work before they start applying and agreeing to them during their senior year. Taking out a loan you can’t pay back and going into debt is something that can haunt you for the rest of your life and is a decision that should be made informed.

Most students also turn sixteen in their junior year, which is the legal age in NC for people to start getting jobs. Students who get a job junior year can be uninformed on how getting a job works as they’ve never done it before. Without the guidance of parents who have financial literacy, understanding documents like the W-2 form, social security deductions, and setting up direct deposit can be very confusing and overwhelming.

Requiring juniors to take an Economics and Personal Finances class would help students understand new jobs, providing the guidance and knowledge they need to make the financial decisions ahead of them both with higher education and in the world outside of high school.

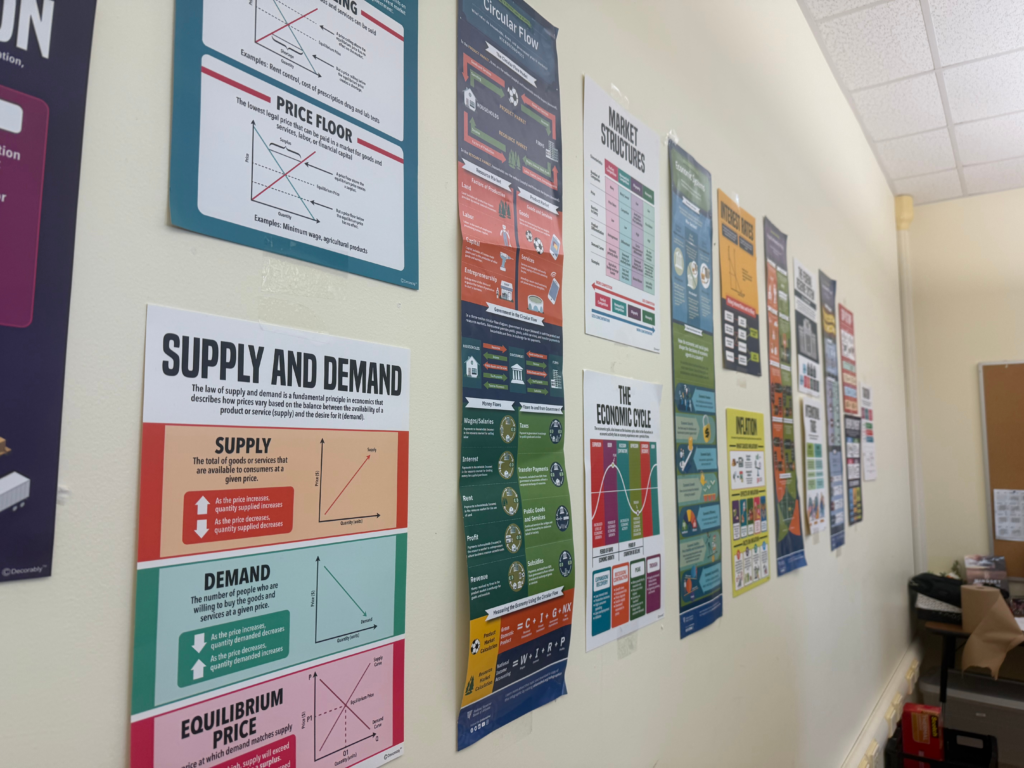

There also seems to be no congruence between EPF classes, with R. J. Reynolds students and Career Center students taking almost entirely different courses. While one class might be making intense projects on different economic systems, another might be coloring in a graphic all day. In some Career Center classes, the course is taught almost to the level of AP micro/macroeconomics, but the class across the hall is two months into the school year, reviewing basic economics.

The same thing is also happening at RJR with the multiple EPF classes learning subjects and topics at completely different times compared to each other. This miscommunication and disjointment could be because of the class’s relative newness and lack of expectations for teachers, but it still leads to too much further confusion among students. The types of things each EPF class learns are extremely varied but often made up of busy work.

If more thought had been put into the creation of the EPF class by the state, then this class would have a huge beneficial impact on students. But, because the state didn’t really think EPF through, students are stuck in classes taught by struggling teachers new to the subject and are taught too late once students have already started making impactful financial decisions. Maybe if the state came back and re-thought the structure of the class, it would be more beneficial, but until then, students will likely continue to pop in their headphones and focus on something else.