Inés Francom

Staff Writer

In September of 2023 the Department of Education: Office of Civil Rights (OCR) sent a resolution letter to the district. In this letter the OCR summarized their findings when looking at Winston-Salem Forsyth County School’s (WS/FCS) disciplinary data and rates over the last 10 years.

“The original [OCR investigation was] about 10 years ago,” WS/FCS Superintendent Tricia McManus said. “The discipline data was being looked at and OCR saw that there was disproportionate discipline data between Black and White students in the district. There was a disproportionate [amount of] out-of-school suspensions (OSS) being assigned [to the racial makeup of the student body].”

This disparity was also noticed by the district in 2020, when data showed that students of color, specifically Black boys, were five times more likely to be suspended than White students. After the resolution was received by WS/FCS, they communicated with the OCR on plans that were already in motion to reverse the disparities the OCR report had brought to light.

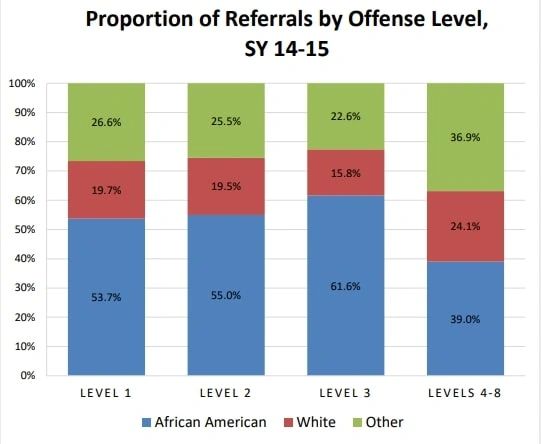

Data reviewed by the OCR showed that Black students receive four times the rate of OSS compared to White students (except during the 2020-21 school year, where it was three times more). Of those OSS’s caused by fighting, Black students received an average of 2.9 days of suspension compared to the average 2.3 days of suspension White students received.

When deciding what consequences behavior like fighting might require, WS/FCS uses a six tier system for evaluating the severity of behavior, with level one being a minor classroom handled event, and level six being a behavior resulting in OSS or expulsion.

The OCR report also found that even when high school students exhibited level three conduct offenses for the first time, 49.9% of Black students received in-school suspensions (ISS), which was 9.6% more than White first time offenders.

“Data is important to illustrate things that aren’t perceived otherwise,” R.J. Reynolds Assistant Principal David Friedman said. “We also have to take it as one piece of the story. It is a great tool for auditing, and the way that we interact with data when we get it, it leads us to ask questions, to inform our processes, to make sure that we’re looking for, we’re identifying and addressing any blind spots that may be present in what we’re doing.”

Using the data WS/FCS collects and the data OCR brought forth, addressing blindspots is what the district is doing. Along with collecting data on referrals, analyzing data collected, and continuing to do their best to ensure fair and equitable discipline policies, WS/FCS has reviewed and revised the 2023 code of Character, Conduct, and Support. A large portion of the code’s changes consist of preventative measures to help students with the underlying causes of behavior before it can manifest in a disruptive way, in the hopes of creating a more equitable and fair environment throughout WS/FCS.

The new code of conduct has added procedures to help prevent incidents from either occurring or escalating.

“There was always a matrix but it has been completely redone,” McManus said. “We actually updated it this year based on feedback groups we did, every school had a team that came to a feedback session, and based on that feedback we’ve updated [the code].”

In order to receive feedback and know what changes and policies work in practice, schools must first get the chance to use the new policies. A process that requires significant time to train administrators and teachers across the district.

“Since the implementation of our new code of conduct and code of character we actually get trained once a month,” R. J. Reynolds Principle Calvin Freeman said. “But with implementation, that training was more intense. You know, we used to spend four days on code implementation. Now, [after the initial implementation] once a month, we get maybe a half day. But it’s something that’s continued.”

One of the preventative measures being taught during training continues the thread of changing classroom mindsets through the restorative practices being taught, and stressing the importance of student-adult interactions to foster better support and engagement with students.

“Hurting people, hurt people,” McManus said. “When kids are feeling great about school, when they’re feeling success, when they’re feeling connected, when they’re feeling engaged, when they have peer groups, and they’re involved, and all of that, they’re not getting into the egregious fighting, they’re not being disrespectful to the adults. So it’s our job to really shift the culture in our buildings so that kids can be successful”

Along with changes the revised code of conduct brings, there have been initiatives to begin leaning more heavily on restorative practice meetings to replace ISS across the district.

“We don’t really call it ISS anymore,” RJR’s Restorative Practice Coordinator (RPC) Melissa Johnson said. “We call it RPC because when they’re here, we’re trying to eliminate the fact that they are missing class time. So for us, it’d be more of, let’s have the conversation, let’s get you back in the classroom.”

The work students do with RPC is all in the hopes of stopping absences, tardies, and other educational hindrances from becoming a pattern for students. While in RPC, students work on creating six-week plans on how to manage problems that disrupt their lives, and overall working with Johnson to get back on track to where they want to be, but that’s not all they do.

“You don’t have to be [causing problems] to use RPC,” Johnson said. “It could be something as simple as you’re having a rough day and you just need someone to talk to. It could just be a challenging day and we can just be challenged. There are times when we have kids who are just like, ‘I’ve got a lot going on and I just need to reset’, and that’s what this space is for; it’s reset and restore.”

Despite the good intentions of the shift towards RPC, the practice of taking students out of the classroom, and the rates of Black students being taken out of the classroom, creates a significant difference in the amount of education students are missing out on.

“I believe that [running classrooms themselves in a restorative manner] removes barriers for some of our students,” Dean of Students Angie Bowman said. “And if you’re removing barriers, you’re creating a more equitable space. So getting rid of those barriers that are sending people to RPC, I think getting rid of any barrier that may keep a kid out of the classroom, keep a kid from being engaged, or send a kid out because they did whatever [is more equitable].”

While teachers are receiving training for restorative practices within the classroom to remove these barriers while still reducing the number of ISS’s assigned, there are over 7,000 employees in WS/FCS to train, making it hard to see an immediate shift. This lack of immediate shift is a theme throughout all actions the district is taking to combat the disproportionate data seen in their weekly analysis of discipline rates.

“It’s very easy to go ‘oh that’s not working or we’re ignoring behavior’ that’s not true at all,” McManus said. “Kids are getting consequences for behavior, but unless we address the root cause, teach, provide mentoring, provide restorative interventions, unless we do that, I’m not sure why anyone would expect the behavior just to change on its own”

While work is being done it will take time for results to be seen in schools. This can create a perception that the issue is being ignored while there are many things happening behind the scenes.

“I honestly think that we’re doing a lot of good work.” Bowman said, “I think that we are very intentional in all of our processes, our procedures. I know that there are systemic barriers that are going to take probably more time than I have left on this earth to get over, but I think as a school we do a really good job of that”

The discrimination shown in the OCR report, and the district’s disciplinary data is not an isolated issue to WS/FCS, it ties into multiple problems and systematic barriers throughout our society.

“The data does tell a story,” Friedman said, “but it’s also a story of our community and where we live.”

Social factors have a huge impact on the actions of students. When days begin and end with frustration, school can become an unintended victim of that frustration.

“When we talk about social factors,” Principal Freeman said, “one of the greatest things we’re talking about is socioeconomics. We look at some of our identifiers, whether students are language learners, whether students are in exceptional children’s programs. And like, what is it about like the learning environment? What is it about like what happens inside of the classroom that can help us eliminate some of the behaviors that lead to out-of-school suspension?”

While schools can’t change the communities they serve, or the problems that their students face outside of school, they can alleviate those problems, and stop them from affecting the educational lives of students. WS/FCS is doing what they can to improve equity in our schools and help support all students, and for their work WS/FCS has seen a slight improvement.

“There are still challenging behaviors occurring,” McManus said, “and there’s still a lot of referrals and out-of-school suspensions being assigned; it’s just that less days are being assigned, and so less days assigned means less instructional time lost. So those are the positives, but we’ve still got a long way to go.”