Briggs Brown

Staff Writer

In recent years questions about test-optional colleges and new test-taking rules, have caused many to look past the deeper-rooted problems of the ACT and SAT that are causing socio-economic injustices across various groups. These standardized tests have received many critiques as they are a main component in college acceptances, especially recently with conversations revolving around affirmative action and admissions fairness.

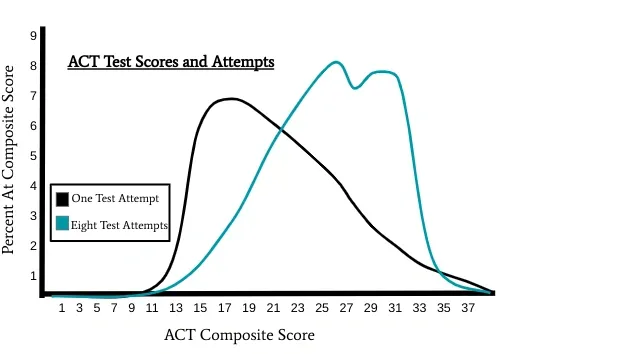

Not long ago, the SAT and ACT introduced a new method of scoring to their tests to have the least amount of prediction error for college success. This new method, called Superscoring, is the process of averaging a test taker’s best test score from each test section to achieve the highest score possible. Superscoring is made to not overstate the abilities of their test takers and overpredict their college success. Conversely, a study conducted by Ty Cruce, Ph.D., and Krista Mattern, Ph.D. in 2020 shows that, “Superscores are typically higher than an ACT Composite score earned from any single test attempt.” This logic conveys the idea that a student who takes the test multiple times for a higher superscore will have an elevated score to represent their ability than a test taker who only takes the test one time. Consequently, the single-time test taker’s abilities will be understated, and lower-income students, who can’t afford to take the test multiple times, will be disproportionately represented.

The ACT costs $88 to take the test with writing, $63 to take the test without writing, $44 for a section retest, $48 for a two-section retest, and $52 for a three-section retest. That is where unfairness is focused. With these prices, the test is difficult for some lower-income families to justify spending money. In contrast, higher-income families can view it as an advantage to achieve the highest score possible as they can afford to pay for multiple test attempts and have higher scores than students who can’t afford multiple attempts. Even if accepted into the ACT Fee Waiver Program to take the test for free, you will be granted only four tests for free if approved each time you apply, which is insignificant relative to the twelve times you can take it. That still is over $700 if a test taker wants to do it the maximum amount of times. This leaves a lower-income test taker at a clear disadvantage.

On a test like the ACT that does not have a guessing penalty, meaning that a wrong answer will not be counted against them, students who can afford extensive test prep courses and multiple test attempts to have a distinct upper hand over those with lower incomes, even if they just guess and play the odds right. This expedites socioeconomic inequalities in access to higher education as lower-income students can “get lucky” with a higher score from guessing.

The SAT has even attempted to address issues of presenting the ability of underprivileged and lower-income test takers. In 2019, the College Board (who oversees the SAT) announced the “adversity score.” This metric was created to provide colleges and universities with contexts about a student’s socioeconomic background by considering factors such as poverty rates and school quality. After the College Board announced that they would incorporate this score into the upcoming test, they received immense backlash claiming that it did not address the root causes of inequality in standardized test taking. Ironically most of this backlash came from the higher-income families who would no longer be as advantaged. Any argument that standardized tests provide a level playing field for students can easily be dismissed by the fact that the SAT itself addressed that there are problems with their test and that it is not fairly representative of underprivileged communities with this scoring metric.

Many proponents still argue that standardized tests provide an objective measurement of students’ capabilities, allowing colleges and universities to review the students on a level playing field. Standardized test advocates argue that the tests help identify talented students who may not have had access to as many opportunities as others. This argument is only valid if you assume every test taker has access to the same resources, test preparation, and amount of test retakes, which unfortunately is not the case.

With growing admissions numbers, admissions officers are in a crunch and need to make decisions based on the limited statistics they are provided which often boils down to relying solely on the standardized test scores as a metric of the student’s ability. Relying purely on the test scores further emphasizes the necessity of the test being fair to all students, and can perpetuate inequalities rather than level the playing field.

Ultimately standardized testing has objectively taken some steps back when it comes to fairness. The introduction of super scoring undeniably gives an upper hand to wealthier test takers who can afford to take the test multiple times. Getting rid of the superstore won’t completely solve the problem, but it will minimize the gap in scores across socioeconomic classes due to test accessibility.